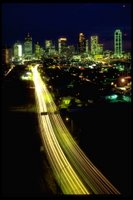

Common sense solutions to our highway doldrums are today's offering from John Tierney in his NY Times op ed. My only real disagreement is with his assertion that should we adopt his reforms, people won't mind paying tolls on previously toll-free Interstates "once they see the cars speeding along in new lanes."

Common sense solutions to our highway doldrums are today's offering from John Tierney in his NY Times op ed. My only real disagreement is with his assertion that should we adopt his reforms, people won't mind paying tolls on previously toll-free Interstates "once they see the cars speeding along in new lanes." Increasing lanes and tolls at peak times will do little in the way of ameliorating traffic jams and speeding up commute times. Chicago took three years to rebuild and re-configure the Kennedy Expressway some years ago in order to speed the flow of traffic. After making things far worse during the three year construction itself, when it was finally finished motorists were hard pressed to see any significant improvement. Today, things are worse than ever, with longer, more bottlenecked rush hours in all directions.

The fact is, we have too many cars and trucks on the roads to imagine that faster rush hour commutes are any longer a possibility. Only much improved and affordable public transportation can potentially lesson the congestion on the roads.

Life, Liberty and Open Lanes

By John Tierney

The New York Times

You may not be enjoying the roads this weekend, but in Washington we see cause to celebrate. You're not just sitting in a traffic jam. You're part of a national birthday party!

Two score and ten years ago, our forefathers brought forth across this continent the Interstate highway system, which you could call America's pyramids except that the pyramids were so puny. Cheops was a piker next to Dwight Eisenhower, the creator of what is reverently known in Congress as the greatest public works project in history.

Eisenhower's granddaughter and great-grandson came to town this week to fete those 46,000 miles of pavement and to listen to speeches by master builders like Don Young, the Alaska congressman who rules the committee that rules the roads. He didn't mention his most famous achievement in the latest highway bill — the "bridge to nowhere" serving a couple of his constituents — but he did brag about the $286 billion cost of the bill.

"I'll guarantee you next time I'm asking for 600 billion," he said, to ecstatic applause from the bureaucrats and highway contractors in the audience. And there, in that one moment of pure pork-barrel bliss, you could see where Eisenhower went wrong — and why you're stuck in traffic today.

The great debate in planning the system was, of course, how to pay for it. Roads had traditionally been a state responsibility, but the feds became more active during the New Deal, when a national system of freeways was drawn up. The planners meticulously calculated that a system of old-fashioned toll roads would never pay for itself because there'd be too little traffic.

A toll road across Pennsylvania, the planners informed Congress in 1939, would attract only 715 cars per day. The next year the Pennsylvania Turnpike opened. It was soon carrying 6,000 cars a day and more than paying for itself, but the federal bias against tolls persisted anyway.

There were good political reasons for Eisenhower to insist that new Interstates be financed by federal gas taxes instead of tolls: drivers have always resented stopping at toll booths, and members of Congress have always enjoyed doling out money. To further win over critics worried about this new federal role, the program was justified on national security grounds (sound familiar?) and named the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways.

Drivers loved the freeways at first, but then the roads deteriorated and the lanes clogged. Engineers wanted to ease congestion by adding lanes, but they couldn't even afford to maintain the existing roads. The gas tax revenue shrank because of inflation and because Congress began earmarking it for thousands of pet projects: parks, promenades, museums, streetcars and bridges to nowhere.

Some road enthusiasts — and their lobbyists — have never stopped dreaming of new federal money, which explains the applause for Young. But more pragmatic engineers know that Young will never get his $600 billion, and that much of it would be wasted anyhow. They also realize that there's no way to prevent traffic jams unless you charge drivers — like airplane passengers — a premium at busy times.

The best way to help drivers is to abandon the Interstate model and adopt two reforms. One is for states to keep the taxes paid by their drivers instead of sending the money to Washington — an idea that has been endorsed by the conservative caucus in the House as a cure for their colleagues' earmarking mania.

The other is to end the taboo against tolls. The highway of the future is the Pennsylvania Turnpike, only with electronic toll collectors instead of booths. By relying on drivers instead of Congress for money, road builders in congested places like Southern California and Houston have finally been adding lanes. By raising the tolls at peak times, they're making sure that traffic keeps moving even at rush hour.

These changes are still tough to make politically because voters have gotten so used to the old toll-free Interstates. But once they see the cars speeding along in new lanes, their nostalgia tends to fade.

The Interstate system was lovely in its youth, and on its birthday I suppose we should fondly recall those days when the concrete was new and the lanes were clear and the price seemed right. But there is no such thing as a freeway. After 50 years, it's time to pay the toll.

Photo credit: John Tierney. (Fred R. Conrad/The New York Times)

Technorati tags: John Tierney, New York Times, Roads, Traffic, Tolls, Automobiles, Commuting, Infrastructure, Congress, Ear-marking, news, commentary, op ed